Syria’s transitional authorities have announced indirect parliamentary elections to be held later this month (most likely between 15-20 September) to elect 140 of the 210 members of the People’s Assembly of Syria. On paper, the electoral process introduces modest but meaningful improvements over earlier efforts by the transitional authorities to broaden political representation. They have pledged multiple consultative phases, mechanisms for appeal, and steps to increase women’s participation.

But these promises are overshadowed by structural ambiguities and unresolved questions that leave the process vulnerable to manipulation. This briefing outlines six key issues to watch during the elections, equipping observers to better assess how the process unfolds and whether it strengthens legitimacy – or risks becoming another top-down exercise that deepens public cynicism.

How We Got Here: The Interim Legislative Framework and Parliamentary Process

Following the fall of the Assad regime on 8 December 2024, the People’s Assembly was dissolved. The new 2025 Interim Constitution of Syria, ratified on 13 March 2025, called for the creation of a provisional People’s Assembly. Under the interim charter, the legislature is authorized to pass new laws, amend or repeal existing legislation, ratify international treaties, and approve the state budget. It may also grant general amnesties and manage its own membership (by accepting resignations or lifting immunity). Decisions are made by majority vote.

With respect to the executive, the assembly exercises limited oversight, such as questioning ministers and reviewing decrees. These powers, however, are tightly constrained: presidential decrees carry the force of law and may only be overturned by a two-thirds majority, ensuring ultimate authority remains with the presidency. In relation to the judiciary, the assembly confirms appointments to the Supreme Constitutional Court, though nominations remain the sole prerogative of the president.

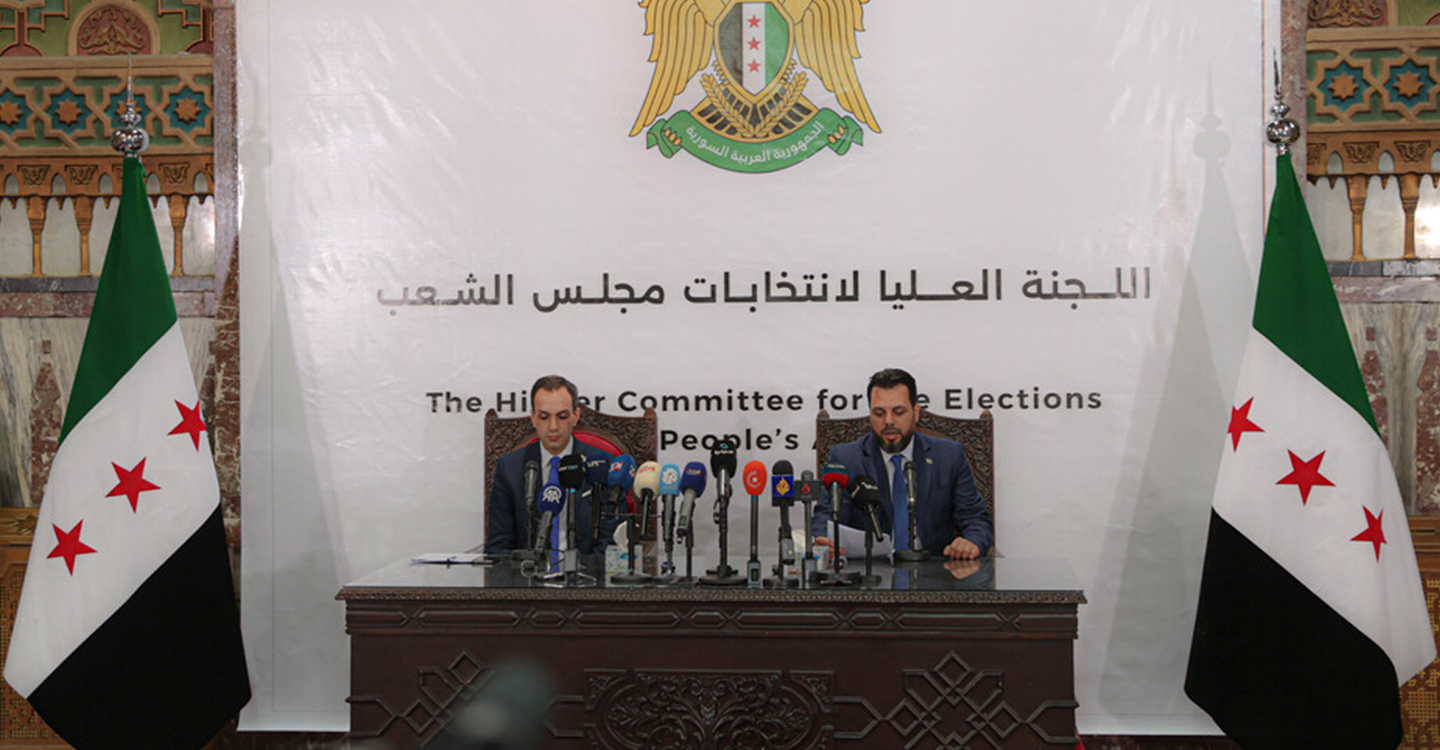

The process to form the new parliament was formally launched on 13 June when interim President Ahmad al-Shara announced the creation of an 11-member Supreme Committee for People’s Assembly Elections (the “Supreme Committee”). The committee is responsible for designing and overseeing an indirect electoral system based on electoral colleges rather than direct public voting.

The assembly was initially set at 150 members but later expanded to 210, following a recommendation by the Supreme Committee after consultations with local communities. Of these, two-thirds are selected through the committee-led process, while the remaining one-third are appointed directly by the president. Seat distribution is based on the population size of Syria’s 14 governorates, according to the 2010 census. Each governorate is further subdivided into electoral districts aligned with its administrative divisions.

Table 1: The distribution of parliamentary seats per governorate

| Governorate | Number of Seats |

|---|---|

| Aleppo | 32 |

| Damascus | 10 |

| Rural Damascus | 12 |

| Homs | 12 |

| Hama | 12 |

| Idlib | 12 |

| Deir ez-Zor | 10 |

| Hasakah | 10 |

| Lattakia | 7 |

| Tartous | 5 |

| Raqqa | 6 |

| Daraa | 6 |

| Sweida | 3 |

| Quneitra | 3 |

| Total | 140 |

The Supreme Committee’s composition and participatory approach mark a shift from previous transitional efforts. The current 11-member body is more diverse than previous transitional initiatives and is not dominated by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), with only two members linked to the HTS-led Salvation Government. While the inclusion of just two women falls far short of equitable, it nonetheless represents a modest step toward greater female participation.

Procedurally, the committee has adopted a more transparent and consultative stance than some of the other committees set up so far by the transitional authorities. It has held public forums and provincial outreach meetings to present its proposed electoral framework and solicit feedback. Several procedural safeguards have also been introduced, including a period for submitting objections related to the selection of electoral bodies and candidate nominations, as well as the establishment of legal appeal committees to review these challenges.

The Electoral Process Explained

According to the temporary electoral law ratified by the Syrian president on 20 August, the process will unfold in three stages. First, the Supreme Committee establishes electoral subcommittees at the district level, based on the seat allocations outlined above. Each subcommittee must include at least three members. The eligibility criteria are broad. These include requirements such as being a Syrian citizen residing in the country, at least 25 years of age, without a criminal record, unaffiliated with the former regime, and not serving in the security forces. While the law requires consultation with local officials and communities, the Supreme Committee ultimately retains final authority over appointments.

Once established, the subcommittees are tasked with forming electoral colleges in their districts. Each college must include 30 to 50 members, selected under similarly vague criteria and consultation procedures. The law does, however, impose quotas: 20 percent of college members must be women, 3 percent must be persons with special needs, and the remaining seats must follow a 70/30 split between professionals and traditional notables. The initial composed list is then submitted to the Supreme Committee, which retains the authority to modify it by replacing candidates or requesting an alternative list from the subcommittee.

Only members of these electoral colleges can nominate themselves for their district’s seat, and only they are allowed to vote. Electoral campaigns are explicitly restricted to the electoral college level and do not extend to the general public. On election day, voting must take place in person, with results announced the same day. The names of winning candidates are then submitted to the president, who finalizes the list and adds the 70 members directly appointed by him.

Although the process was meant to take place nationwide simultaneously, the Supreme Committee announced on 23 August that elections would not be held in Sweida or in most parts of Hasakah and Raqqa, citing insecurity and political deadlock. The committee said that voting in these areas would be postponed until conditions allow. In the meantime, the legislative council will be reduced to 201 members.

Six Developments to Monitor

With theannouncementofthenames of the members of the district subcommittees on 3 September, the electoral process is now moving full steam ahead toward forming the electoral colleges. Although no exact date has been set for the vote, the Supreme Committee has suggested it could take place between 15 and 20 September. With only weeks or possibly days to go, here are some of the key issues to watch during the final stage of the process.

1- Formation of Electoral Bodies

Given the immense influence subcommittees will have in selecting electoral colleges, the profile of their members will be critical. Their small size magnifies the power of individual members and makes them highly vulnerable to political manipulation. Equally important is the profile of the college members themselves. Who are these individuals? How popular are they? What political affiliations do they hold? Were they selected in a balanced way, or do they give undue advantage to certain actors or parties?

2- Monitoring and Oversight

Observers are expected to play a role, but details remain vague. Who will appoint them? How skilled are they? Which stages will they monitor? If observation is confined to the final vote, oversight will be largely symbolic. The greatest risks of manipulation occur earlier, during the formation of subcommittees and electoral colleges. Without independent oversight at every stage, transparency and trust will remain elusive.

3- Representation of Areas Beyond Damascus

Perhaps the most delicate issue is how to represent territories outside Damascus’s control, including Sweida, Hasakah, and Raqqa. The president may appoint representatives to avoid their exclusion, but without local buy-in, this could fuel mistrust and further entrench fragmentation. It will, therefore, be important to see how these areas are represented and what impact that will have on the parliament’s credibility and its relations with de facto authorities.

4- Enforcement of Quotas

The draft law sets quotas for the composition of the electoral colleges of 20 percent for women, 3 percent for people with special needs, and a 70/30 split between professionals and traditional notables. However, these quotas appear to apply only to the composition of the electoral colleges, primarily as voters, since running for seats is optional. It remains unclear whether similar quotas will be applied to the composition of the legislative body itself.

Holding indirect elections at the district rather than the provincial level makes it even less likely that these targets will be met. Most districts will have only a single seat, increasing the chances of traditional elites dominating the process at the expense of technically qualified professionals, while leaving women well below the 20 percent threshold. Without enforcement, these quotas risk becoming little more than symbolic gestures.

5- Profiles of Presidential Appointees

With one third of parliament directly appointed by the president, understanding the profile of these appointees, their independence from the president, and the objectives behind their selection will be crucial. This is especially important given that under the interim constitution, presidential decrees carry the force of law and can only be overturned by a two-thirds majority. This makes the profile of presidential appointees even more critical: if the president selects individuals subject to his influence, he could issue laws through decrees without effective challenge. This is especially concerning at this transitional moment, when the country’s legal and institutional framework is being rewritten. Another consideration to examine is whether presidential appointees will be chosen to ensure demographic, gender, or religious representation or to provide the assembly with essential expertise. The outcome will shape both the parliament’s legitimacy and its effectiveness.

6- Local Perception

The format of the process – with its emphasis on an indirect process – makes it difficult to gauge the popularity of the elections and the legitimacy of their outcomes due to the lack of direct public participation. In the absence of this, various indirect measures could be used. These include the number of appeals filed to challenge candidates, the level of competition among electoral members, the involvement of local elites, and any boycott announcements or withdrawals from the process.

Other indicators could include the popularity of electoral college members and how well they represent their communities. Without formal surveys or semi-structured interviews to gather public opinion on these issues, monitoring social media platforms could provide one accessible alternative for assessing perceptions and reactions, though we have seen that social media is being heavily manipulated in Syria.

Syria’s legislative reboot is a test not only of process but also of the transitional government’s political will. Its success or failure will hinge on the transparency of its procedures, the integrity of those leading it, and the inclusiveness of its outcomes. This moment could either legitimize a fragile transition or deepen long-standing public cynicism.